This text is taken from the book ‘Enjoy Hatha Yoga’ by Khun Reinhard.

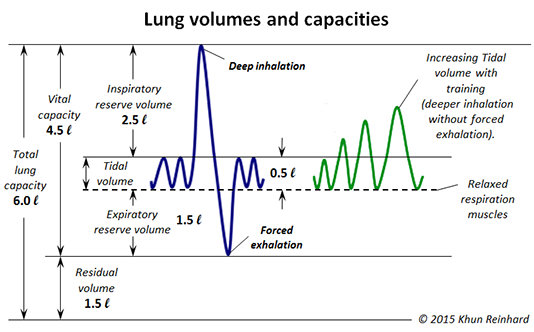

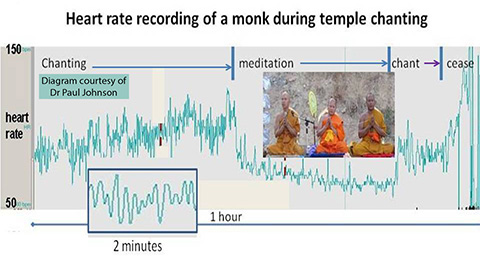

A general introduction, first into the physiological basics of respiration, then into yoga-breathing is given.

More details regarding the physiology of respiration are provided in the free pdf-version. Please find the download link at the bottom of this page.

The Breath-body coordination page of this website introduces exercises to coordinate breathing with bodily movements.